- Home

- Technical College

- MOTOR TECHNOLOGY

- Difference between Open-Loop Control and Closed-Loop Control

Difference between Open-Loop Control and Closed-Loop Control

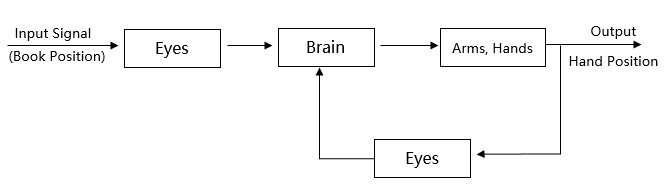

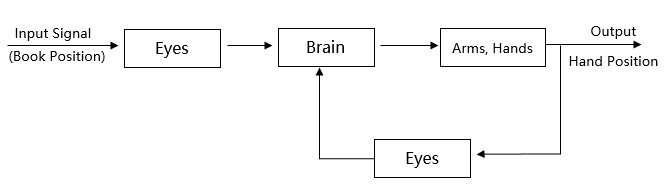

Open-loop and closed-loop control are two fundamental structures in automatic control systems. The key distinction is the presence of a feedback mechanism, which allows a system to adjust its inputs in real time based on output. The following focuses on the principles of open-loop and closed-loop control.  Figure A. Block diagram of the feedback control system for people to retrieve books The process of feeding an output signal back to the input and comparing it with the original input to generate an error signal is known as feedback. When the feedback signal is subtracted from the input to reduce this error, it is called negative feedback; if it adds to the input, it is called positive feedback. Closed-loop control is a process that utilizes negative feedback to act on this error. The inclusion of feedback from the output creates a closed signal path, which gives the method its name. Its defining characteristic is that any deviation of the controlled variable from its desired setpoint will automatically trigger a control action to reduce or eliminate that error, driving the output toward the desired value. Consequently, closed-loop systems are capable of suppressing both internal and external disturbances, resulting in high control accuracy. However, these systems require more components and circuitry, which complicates performance analysis and design. Despite these challenges, closed-loop control remains a vital and widely applied method and is the primary subject of study in automatic control theory. A function recorder provides a practical example of a closed-loop control system. It is a general-purpose instrument that automatically plots the relationship between two electrical quantities on a Cartesian coordinate system. Additionally, it is equipped with a paper feed mechanism to plot an electrical quantity as a function of time. A function recorder typically consists of a converter, measuring elements, amplifying elements, a servo motor-tachometer unit, a gear train, and a rope wheels. It operates on the principle of negative closed-loop control, as shown in Figure B. The system input is the voltage to be recorded, and the controlled object is the recording pen, whose displacement is the controlled variable. The system's task is to control the pen's displacement to create a voltage curve on the recording paper.

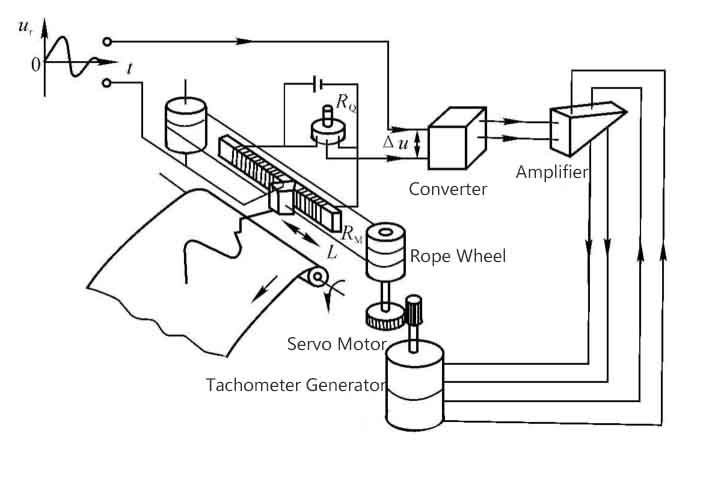

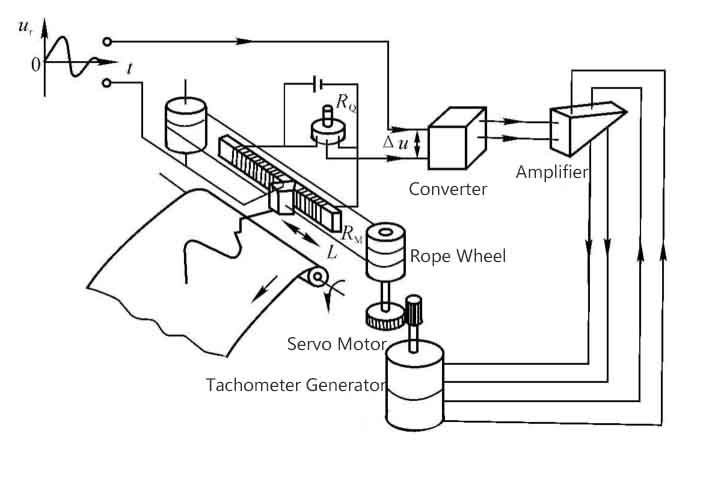

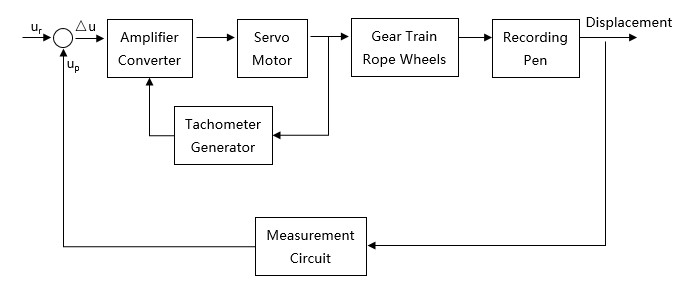

Figure A. Block diagram of the feedback control system for people to retrieve books The process of feeding an output signal back to the input and comparing it with the original input to generate an error signal is known as feedback. When the feedback signal is subtracted from the input to reduce this error, it is called negative feedback; if it adds to the input, it is called positive feedback. Closed-loop control is a process that utilizes negative feedback to act on this error. The inclusion of feedback from the output creates a closed signal path, which gives the method its name. Its defining characteristic is that any deviation of the controlled variable from its desired setpoint will automatically trigger a control action to reduce or eliminate that error, driving the output toward the desired value. Consequently, closed-loop systems are capable of suppressing both internal and external disturbances, resulting in high control accuracy. However, these systems require more components and circuitry, which complicates performance analysis and design. Despite these challenges, closed-loop control remains a vital and widely applied method and is the primary subject of study in automatic control theory. A function recorder provides a practical example of a closed-loop control system. It is a general-purpose instrument that automatically plots the relationship between two electrical quantities on a Cartesian coordinate system. Additionally, it is equipped with a paper feed mechanism to plot an electrical quantity as a function of time. A function recorder typically consists of a converter, measuring elements, amplifying elements, a servo motor-tachometer unit, a gear train, and a rope wheels. It operates on the principle of negative closed-loop control, as shown in Figure B. The system input is the voltage to be recorded, and the controlled object is the recording pen, whose displacement is the controlled variable. The system's task is to control the pen's displacement to create a voltage curve on the recording paper.  Figure B. Schematic diagram of the function recorder In Figure B, the measuring element is a bridge-type measuring circuit consisting of potentiometers RQ and RM. The stylus is fixed to the slider of potentiometer RM. Therefore, the measuring circuit's output voltage up, is proportional to the stylus's displacement. When the input voltage ur varies, an offset voltage △u=ur - up, is generated at the input of the amplifier element. This amplified error signal drives the servo motor, which moves the stylus via a gear train and cable-pulley system, thereby reducing the error voltage. When the offset voltage, △u= 0 the motor stops, and the stylus also stops. At this point, up=ur, indicating that the stylus's displacement corresponds to the input voltage. If the input voltage varies continuously over time, the stylus will trace a curve that varies continuously over time. The structure of the function recorder is shown in Figure C. The feedback signal from the tachometer generator in this figure is a voltage proportional to the motor speed, which is used to increase damping to improve system performance.

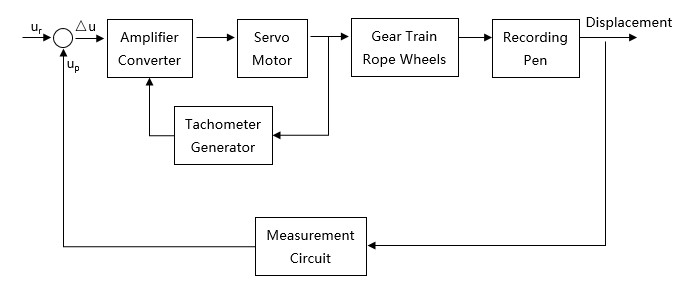

Figure B. Schematic diagram of the function recorder In Figure B, the measuring element is a bridge-type measuring circuit consisting of potentiometers RQ and RM. The stylus is fixed to the slider of potentiometer RM. Therefore, the measuring circuit's output voltage up, is proportional to the stylus's displacement. When the input voltage ur varies, an offset voltage △u=ur - up, is generated at the input of the amplifier element. This amplified error signal drives the servo motor, which moves the stylus via a gear train and cable-pulley system, thereby reducing the error voltage. When the offset voltage, △u= 0 the motor stops, and the stylus also stops. At this point, up=ur, indicating that the stylus's displacement corresponds to the input voltage. If the input voltage varies continuously over time, the stylus will trace a curve that varies continuously over time. The structure of the function recorder is shown in Figure C. The feedback signal from the tachometer generator in this figure is a voltage proportional to the motor speed, which is used to increase damping to improve system performance.  Figure C. Function Recorder Structure Diagram

Figure C. Function Recorder Structure Diagram

Open-Loop Control

Open-loop control describes a process where there is only a forward signal path from the controller to the controlled object, with no reverse interaction. A system designed in this way is called an open-loop control system. Its characteristic is that the system's output has no influence on the control action. Open-loop control systems can be implemented based on either a setpoint control or a disturbance compensation principle. An open-loop control system operating on a setpoint, the control action is generated directly from the input, resulting in a predictable output for any given input. Control accuracy depends entirely on the components used and the accuracy of their calibration. Therefore, this type of system cannot automatically correct for deviations and exhibits poor disturbance rejection. However, due to its simple structure, easy adjustment, and low cost, this control method still has some practical value when accuracy requirements are low or the impact of disturbances is minimal. For that reason, many automated systems in commercial and industrial sectors—such as vending machines, automatic washing machines, production lines, CNC lathes, and traffic lights controllers—are based on open-loop control. An open-loop control system based on disturbance control uses measurable disturbances to proactively generate a compensation signal, reducing or offsetting the effect of disturbances on the output. This control method is also known as feedforward control. For example, in a standard DC motor speed control system, the rotational speed typically drops as the load increases, a change that is directly related to the armature current. If we can measure the current change caused by the load and generate an additional control effect based on its magnitude to compensate for the resulting speed drop, we can create an open-loop control system based on disturbance control. This open-loop control method directly obtains information from the disturbance and uses it to change the controlled variable, offering good disturbance rejection and high control accuracy, but it is only applicable when the disturbance itself can be measured.Closed-Loop Control

Closed-loop control is a fundamental and widely used strategy in electromechanical systems. In this type of system, the control device exerts control over the controlled object based on feedback from the controlled variable, continuously correcting deviations in the controlled variable to achieve control of the controlled object. This is the principle of closed-loop control. In fact, all human activities are governed by the principle of closed-loop control, making the human body a highly complex closed-loop system. Everyday actions, from picking up a book to steering a car smoothly down a road, are all based on this principle. Below, we will dissect the process of picking up a book to illustrate the underlying closed-loop mechanism. As shown in Figure A, the book's position serves as the command for the hand's movement; this is the input signal (or reference signal). To begin, the eyes visually track the hand's position relative to the book and send this information to the brain (position feedback). The brain then calculates the discrepancy, generating an error signal. Based on this error, the brain issues commands (the control action) to the arm muscles, which move the hand to progressively reduce the distance (the error). This process repeats as long as an error exits, continuing until it is reduced to zero and the hand grasps the book. As you can see, the brain controls the hand by using a perceived error to generate corrective actions that continually reduce that error. Therefore, closed-loop control is essentially control by error correction. Its principle is precisely that: to control based on deviation. Figure A. Block diagram of the feedback control system for people to retrieve books The process of feeding an output signal back to the input and comparing it with the original input to generate an error signal is known as feedback. When the feedback signal is subtracted from the input to reduce this error, it is called negative feedback; if it adds to the input, it is called positive feedback. Closed-loop control is a process that utilizes negative feedback to act on this error. The inclusion of feedback from the output creates a closed signal path, which gives the method its name. Its defining characteristic is that any deviation of the controlled variable from its desired setpoint will automatically trigger a control action to reduce or eliminate that error, driving the output toward the desired value. Consequently, closed-loop systems are capable of suppressing both internal and external disturbances, resulting in high control accuracy. However, these systems require more components and circuitry, which complicates performance analysis and design. Despite these challenges, closed-loop control remains a vital and widely applied method and is the primary subject of study in automatic control theory. A function recorder provides a practical example of a closed-loop control system. It is a general-purpose instrument that automatically plots the relationship between two electrical quantities on a Cartesian coordinate system. Additionally, it is equipped with a paper feed mechanism to plot an electrical quantity as a function of time. A function recorder typically consists of a converter, measuring elements, amplifying elements, a servo motor-tachometer unit, a gear train, and a rope wheels. It operates on the principle of negative closed-loop control, as shown in Figure B. The system input is the voltage to be recorded, and the controlled object is the recording pen, whose displacement is the controlled variable. The system's task is to control the pen's displacement to create a voltage curve on the recording paper.

Figure A. Block diagram of the feedback control system for people to retrieve books The process of feeding an output signal back to the input and comparing it with the original input to generate an error signal is known as feedback. When the feedback signal is subtracted from the input to reduce this error, it is called negative feedback; if it adds to the input, it is called positive feedback. Closed-loop control is a process that utilizes negative feedback to act on this error. The inclusion of feedback from the output creates a closed signal path, which gives the method its name. Its defining characteristic is that any deviation of the controlled variable from its desired setpoint will automatically trigger a control action to reduce or eliminate that error, driving the output toward the desired value. Consequently, closed-loop systems are capable of suppressing both internal and external disturbances, resulting in high control accuracy. However, these systems require more components and circuitry, which complicates performance analysis and design. Despite these challenges, closed-loop control remains a vital and widely applied method and is the primary subject of study in automatic control theory. A function recorder provides a practical example of a closed-loop control system. It is a general-purpose instrument that automatically plots the relationship between two electrical quantities on a Cartesian coordinate system. Additionally, it is equipped with a paper feed mechanism to plot an electrical quantity as a function of time. A function recorder typically consists of a converter, measuring elements, amplifying elements, a servo motor-tachometer unit, a gear train, and a rope wheels. It operates on the principle of negative closed-loop control, as shown in Figure B. The system input is the voltage to be recorded, and the controlled object is the recording pen, whose displacement is the controlled variable. The system's task is to control the pen's displacement to create a voltage curve on the recording paper.  Figure B. Schematic diagram of the function recorder In Figure B, the measuring element is a bridge-type measuring circuit consisting of potentiometers RQ and RM. The stylus is fixed to the slider of potentiometer RM. Therefore, the measuring circuit's output voltage up, is proportional to the stylus's displacement. When the input voltage ur varies, an offset voltage △u=ur - up, is generated at the input of the amplifier element. This amplified error signal drives the servo motor, which moves the stylus via a gear train and cable-pulley system, thereby reducing the error voltage. When the offset voltage, △u= 0 the motor stops, and the stylus also stops. At this point, up=ur, indicating that the stylus's displacement corresponds to the input voltage. If the input voltage varies continuously over time, the stylus will trace a curve that varies continuously over time. The structure of the function recorder is shown in Figure C. The feedback signal from the tachometer generator in this figure is a voltage proportional to the motor speed, which is used to increase damping to improve system performance.

Figure B. Schematic diagram of the function recorder In Figure B, the measuring element is a bridge-type measuring circuit consisting of potentiometers RQ and RM. The stylus is fixed to the slider of potentiometer RM. Therefore, the measuring circuit's output voltage up, is proportional to the stylus's displacement. When the input voltage ur varies, an offset voltage △u=ur - up, is generated at the input of the amplifier element. This amplified error signal drives the servo motor, which moves the stylus via a gear train and cable-pulley system, thereby reducing the error voltage. When the offset voltage, △u= 0 the motor stops, and the stylus also stops. At this point, up=ur, indicating that the stylus's displacement corresponds to the input voltage. If the input voltage varies continuously over time, the stylus will trace a curve that varies continuously over time. The structure of the function recorder is shown in Figure C. The feedback signal from the tachometer generator in this figure is a voltage proportional to the motor speed, which is used to increase damping to improve system performance.  Figure C. Function Recorder Structure Diagram

Figure C. Function Recorder Structure Diagram