How do Hall sensors and incremental encoders differ?

Both Hall sensors and incremental encoders are motion detection devices used to measure position and speed, but they differ significantly in terms of working principles, measurement accuracy, applications, and cost structure.

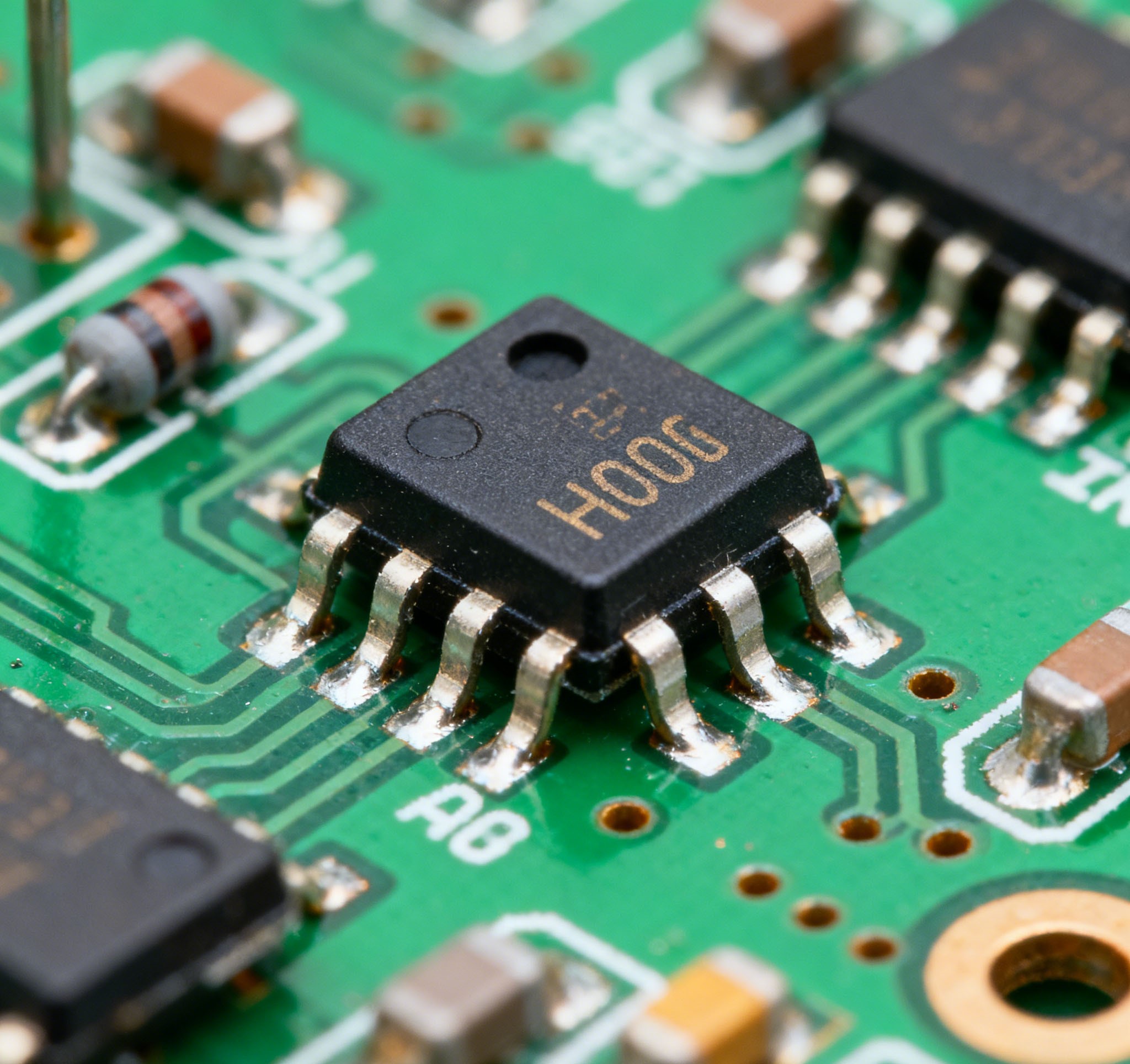

Hall Sensors

A Hall sensor is a magnetic-sensitive device based on the Hall effect, which outputs a digital signal when exposed to a magnetic field. In motor control applications, two to three Hall sensors are typically embedded in the motor stator and sequentially triggered by the rotating magnetic field of the permanent magnet rotor, generating three square wave signals with a 120° electrical phase difference. Hall sensors offer several advantages, including low cost, simple circuit design, high reliability, and resistance to environmental pollutants. However, they also have significant limitations: position detection accuracy is relatively low, as they can only detect the rotor's magnetic pole sector position. For instance, in a 4-pole pair motor, only 24 discrete position states are provided per revolution, resulting in very coarse resolution. Speed measurement is based on timing the transitions of the signal, with noticeable errors at low speeds. Additionally, the motor requires a specific startup sequence (e.g., forced alignment) to determine the initial position, making it unusable immediately after power-on. In summary, the positioning method of Hall sensors is similar to dividing the circumference into 6 or 8 sectors: they can determine the sector where the object is located but cannot provide precise positioning within that sector.

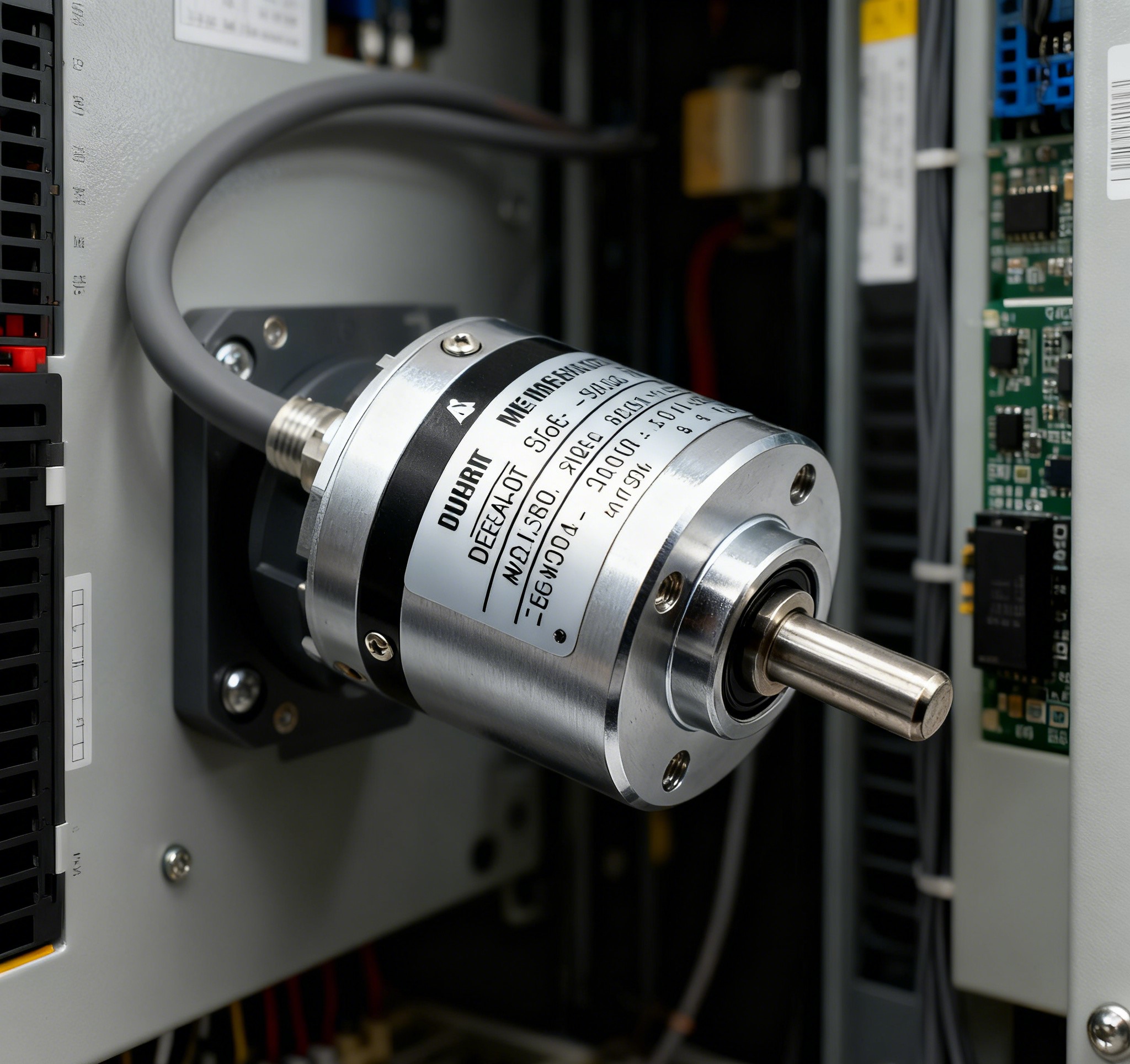

Incremental Encoders

Incremental encoders convert mechanical displacement into electrical pulse signals through an integrated optical or magnetic code disk. The core component is a code disk engraved with a precision grid, which generates two phase-shifted A and B pulse signals with a 90° phase difference during rotation through photoelectric or magnetic sensing. This key phase difference allows the system to accurately determine the direction of rotation: the direction is determined by identifying the phase lead relationship between the A and B pulses. Position information is obtained by counting the pulses, and the speed is calculated based on the pulse frequency over a unit time period. Additionally, the encoder features a Z-phase reference signal, outputting one index pulse per revolution, providing a mechanical origin reference for the system. However, this design does not have a power-off position memory function.

Incremental encoders offer advantages such as high precision, excellent resolution, and fast dynamic response, making them suitable for meeting the real-time demands of complex closed-loop control systems. However, their limitations are also evident: they are relatively expensive; due to the use of a relative counting mechanism, abnormal pulse acquisition can lead to cumulative errors, necessitating correction with the Z-phase signal; and after a system restart, a homing operation is required to re-establish the position reference. Figuratively speaking, an incremental encoder is like a ruler with precise markings but no absolute zero point, it can accurately measure the number of increments and direction, but it must rely on a specific marker point (Z-phase) to determine absolute coordinates.

The following table compares the differences between Hall sensors and incremental encoders:

Comparison Table of Key Differences Between Hall Sensors and Incremental Encoders

| Features | Hall Sensors | Incremental Encoders |

| Working Principle | Based on the Hall effect, it detects the presence and polarity changes of a magnetic field. | It generates pulse signals with a 90° phase difference using a grating or magnetic scale. |

| Output Signals | Typically, three digital signals with a 120° phase difference (used for brushless motors). | Two quadrature pulse signals (A and B) and an index signal (Z). |

| Accuracy/Resolution | Position detection accuracy is very low. It can typically distinguish only a few discrete position points (e.g., 24 for an 8-pole motor). | Resolution is very high. It is determined by the pulses per revolution (PPR), ranging from hundreds to tens of thousands. |

| Function | Primarily used for commutation and rough speed estimation. | Used for precise position and speed feedback, and can detect direction. |

| Initial Power-on Position | Unknown. An additional startup procedure (e.g., alignment) is required to determine the rotor position. | Unknown. The Z-phase index pulse must be located to obtain the absolute position. |

| Cost | Low | Medium to high (increases with higher accuracy) |

| Typical Applications | Electronic commutation of brushless DC (BLDC) motors. | Servo motors, stepper motors, high-precision speed control and position control. |

| System Complexity | Simple | Relatively complex, requiring the processing of high-frequency pulses and counting. |

Selection Strategy for Motion Control Sensors

In practical applications, the choice between Hall sensors and incremental encoders depends on a comprehensive trade-off between cost, accuracy, and system performance.

Hall sensors should be prioritized in the following scenarios:

1) Basic motor control with low accuracy requirements: When the core application is to control the stable operation of a brushless DC motor, without stringent requirements for position and speed accuracy, Hall sensors are an ideal choice. Typical applications include computer cooling fans, drone propellers, power tools, and water pumps.

2) When project cost is sensitive: In large-scale mass production or projects with strict cost control, Hall sensors are often the preferred solution due to their cost-effectiveness and simple circuit design.

Incremental encoders are usually more suitable in the following scenarios:

1) High-precision closed-loop control is required: When the application requires precise speed control or position positioning, an incremental encoder must be used. It is indispensable in equipment such as industrial robots, CNC machine tools, servo drive systems, and precision conveyors.

2) Real-time high-resolution feedback is required: Any dynamic control system that needs to obtain precise motor rotation angles and speeds in real time should rely on the high-resolution pulse signal provided by the incremental encoder.